New Places, Old Mistakes: How Bad Architecture Moved from Physical to Digital

plus, a request you'll rarely see on Substack

(the “reallly unusual on Substack” request is at the end, don’t miss it!!!).

"The same automatic, old script that has produced socially zoned, polluted, and dehumanizing urban environments throughout the planet keeps unfolding on a higher level, including the metaverse, as Marco Fioretti explains in this issue."

What you just read is the presentation in the Journal of Biourbanism of an essay of mine, of which this post is just a summary. The complete version, with references to all sources, was recently published in Volume X, No. 1 & 2 of the Journal.

Human beings thrived in cities full of variety. Then, they lost them

To begin with, I'll summarize the common thesis of a few experts of architecture and urbanism I discovered a couple years ago: non-complex urban systems alienate, dumb down and control both individuals and whole societies, and in extreme cases can even push them toward civil war.

The root reason is that human physiology never evolved to cope with environments that treat even human beings as objects without variety. This is an application of the Law of Requisite Vriety, first expressed by W. Ross Ashby in 1956, which states that "any system that governs another, larger complex system must have a degree of complexity comparable to the system it is governing".

This also applies to cities which, argues N. Salingaros, consist of two complex systems that govern each other.

The first system is the human individuals and society that design and govern the other system, which is the built environment. In turn, that environment governs people and society, because its geometry contains and controls the activities of its users through physical spaces and their psychological impact.

Since Ashby's Law also applies to human habitats, the monotonous, drastically simplified built environments made of non-interacting units that became much more common worldwide after World War II will only sustain equally constrained people, making it easier to mold them into any form.

How are those people constrained, exactly? Today's "optimized" urban spaces (and time), according to M. Marra, prioritize compulsive motion, light, actuality, and reification. They saturate the senses by fostering and constantly mixing roars from the crowds.

This process, says Marra, started with the Enlightenment - a movement that, in order to fight a primeval fear for what is unknown and does not surrender to simplifications, started a programmatic erasure of differences, invisibility and shadows of every kind. Modern cities dematerialize life, reducing human-inhabited space to economics, exchange, and usury value.

This reduction is both a prerequisite and a consequence of industrialization, because uniform places are a much better fit for production, accumulation, consumption, and dissipation.

Still quoting Marra, it is that flattening of urban space that initiated the compelling need for speed, the excess of information, the disaggregation of the social fabric's continuity (via zoning and gentrification), and, on a deeper layer, the atomization of the individual and its severance from every connecting background, including collective memory and narrative.

Going even further than Marra and Salingaros, Syrian architect Marwa al-Sabouni has described in her book "The Battle for Home" and the corresponding TED Talk, how urbanism and architecture direct human activity so much that they can actively contribute to "prime" people for war, or do just the opposite.

Settlement, identity and social integration, says al-Sabouni, are all the producer and product of effective urbanism that, without negating their identities, forces people to respect the diversity of the other people around them, and the mutual interest of living together in harmony.

Designing cities, instead, as though they were the temporary shacks of nomads, takes away continuity and collective memory. That's the same as taking away citizenship, because nomads belong to, and find reference points in, only tribes, not places.

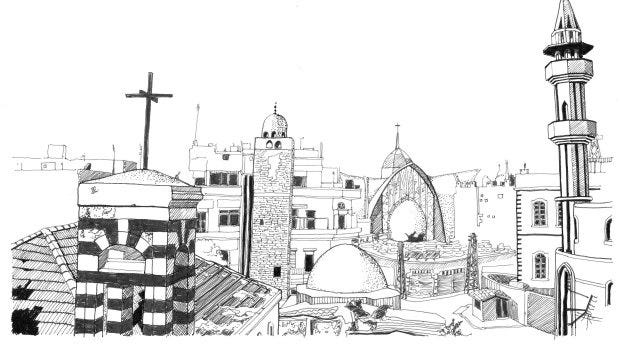

Al-Sabouni illustrates this point by comparing the old and new urbanization of Syrian Cities like Homs and Aleppo.

In old Homs, or Aleppo, drinking fountains on the streets, benches to sit on, and the cool shade of trees nurtured a shared morality and understanding of public goods. Markets with many facing and adjoining shops, a shared route under one ceiling and one sky for all, helped and trained all merchants to be kind. Mosques and Churches placed in the same streets or squares were not affirmations of rival "identities", but signs of mutual accommodation, freeing both Muslims and Christians from ever having to prove their social status through their religions.

Then, modern urbanization took over, destroying those cities before war even began. When the Syrian Civil War started in 2011, almost half of the Syrian population was living inside anonymous concrete barracks, in zones all distinct by class, creed, ethnicity, or other equally sectarian differences, and all disconnected from the city centers and from each other.

Having no pre-existing identity attached to them other than the segregated ones of their new, freshly displaced residents, the new neighborhoods produced social disaffection, social stagnation and introversion.

This segregation divided people who had been previously able to talk with each other long enough to push them into the precursor of actual civil war: a "war of identities based on... a desperate need to define identity not by what everybody shares but by what excludes others".

Digital cities? Same old, same old

At the end of the day, all those experts say the same thing: forcing monotony and fragmentation on human environments is bad, because urbanism based on zoning by class, race, religion and similar criteria can only bring serious instability, everywhere it is practiced.

Reading Salingaros, Marra and al-Sabouni I immediately saw, and wrote the essay to help everybody do the same, truly striking similarities between the alienation and war-facilitating effects of bad architecture and the mental health issues, exaltation of identity politics and political polarization enabled by current social media.

In other words, if today we have toxic social media, it's because we let unprepared people build those digital cities all by themselves, in the same ways that were already toxic centuries before the invention of software: the ways that "prioritize compulsive motion, light, actuality, reification [and] saturate the senses by fostering... roars from the crowds".

Platforms designed to intensify user atomization and exasperation can only produce the same dialogue-killing "desperate need of definition by what excludes others" of urban segregation by ethnicity or any other criterion. "Nomads belonging to, and finding reference points in only tribes, not place" is a great one-sentence summary of the extremes that identity politics would have hardly reached so quickly, without Twitter and other flame-war accelerators.

At the same time, be they physical or digital, ugly, monotonous, and self-segregating places make people sad, angry and easier to control. Just like the alienating cities described by Marra, environments like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or TikTok, can only make of trust-based communities "the scarcest thing in the world".

How do we fix this mess?

Can we redesign digital cities to make them provide the same benefits of "old" physical cities? Above all, should we? Where? Here are, again from the full essay, the starting points for a discussion we cannot delay anymore.

To begin with, one big reason why people are drawn to digital squares is exactly the fact that their physical ones suck - if they even still exist. Many millions of people "replaced the sidewalk with the timeline" because they have literally no more sidewalks to walk on, or reasons to do it. Digital squares exploit for profit the pre-existing urge to avoid alienating physical places, which is the dumbest thing to do, because democracy is where bodies are.

Speaking of digital squares and cities, instead, the long term solution could be to overcome the very concept of "social platforms" in favor of permanent, personal clouds.

In the meantime, instead of pointless proposals to break up social media companies or guarantee data portability we should make adversarial interoperability mandatory. This measure alone would make social media much less addictive and time consuming, and force media corporations to treat their users better.

At the same time, it's necessary to acknowledge, together with all the similarities, the crucial difference between bad physical cities and bad digital ones.

In physical slums, segregation and disgregation happen thanks to physical barriers - from zoning to lack of roads or public transit - that prevent integration because they are very visible, and take too much time or money to dismantle, or get around.

In digital cities, instead, (self-) segregation, hysteria and alienation happen exactly in the opposite way: the barriers that would prevent such problems do not exist, while those that make them happen not only are invisible, but take zero time and money to build, while still giving people, through instantaneous "communication", illusions of freedom and self-realization.

The consequence of this fundamental difference is that, in order to become or return healthy places, physical and digital cities must follow opposite strategies.

Physical cities must build or restore among their various communities closeness, interaction and concrete opportunities to really understand and support each other; this means reducing what generates or perpetuates segregation and hostility, like zoning, lack of public transit and so on.

Social media are just warp-speed banlieues

Dgital cities, instead, should do two things: first, get rid of endlessly customizable, but invisible barriers that are way too easy to erect, by both the owners and the residents of said cities, that is (in a nutshell!) profiling and algorithm-driven feeds. The other is enforcing speed limits just like physical cities do.

Instantness, that is the lack of physical limits on quantity and speed of "communication" (NOT on its content, which would be censorship!) but also on the ability to erect walls, is exactly what makes infinitely easier for everybody to get angry, or totally indifferent, about everybody else.

Whatever fringe priority or frustration one may have, being instantaneously connected to all and only the other humans with the same priorities or frustrations, and nobody else, is a perfect digital replica of the "anonymous concrete barracks [each self-segregated] by class, creed, ethnicity, or other equally sectarian differences" that al-Sabouni exposes as "active precursors of war".

The only discourse that this digital urbanism of instantaneous self segregation facilitates is the same, only choice left to the Homs newcomers: affirming identity "not by what everybody shares but by what excludes others."

When scrolling through monotony replaces strolling among variety, and confirmation feedback is instantaneous, nobody ever crosses or stays long enough in any "public reality" or varied place. That's why an essential step to make digital variety real and really "liberating, without top-down control," as Salingaros puts it, may be to just slow down social media, to a speed human brains can handle.

What if every "group comment", that is every single comment to every YouTube video, tweet, Instagram post... did not appear instantaneously to every other users, but five or ten minutes later, by design? (continues here, on page 129).

Now, the unusual request

In general, the subscription economy is bad for society, because too many paywalls just leave the field open to free news that make extremists.

More down to earth, the subscription econony just doesn’t work, and cannot work, for enough people. Getting a subscription to every source of content, just to access a few movies or posts from that source would be too complicated and overwhelming even if it weren’t just too expensive (1,000$/year on average in the US? No way!). Hence, my request:

if you find this and my Substack archive promising enough to deserve a paid subscription here, by all means go for it, thanks!

however, in my own personal interpretation of the 1,000 True Fans Theory, I also strongly suggest every reader who feels it would be good to give me as much time as possible to make more of this or similar works, to…

just go for a one time donation for any amount you want, via PayPal (mfioretti@nexaima.net) or LiberaPay (*). No strings attached, no risks of automatic renewals, and the right, affordable price for everybody, that is just what you can and want to chip in right now, subscriptions be damned!

I’m serious. Let’s make this darned “attention economy” sustainable for everybody, shall we? Set an example. Just give me one donation, do the same for every other “creator” (God, how I hate that word…), and let’s hope we meet again sometime.

(*) If you prefer other methods, just contact me.

You ask good business questions, which I don't know the answer to.

Problem is neither does my alma mater, the Medill School of Journalism. They have never dealt with business models because Northwestern also has a business school, which I guess calls dibs on such questions. Just got a note from them today, bragging that they were studying "new local media" but weren't looking to spread any business success stories, just journalism ones. I'm afraid I went off on them a bit.

I have always been a pain in the ass.

Important addition! I have been notified just now of a similar article, of which I knew absolutely nothing. Haven't fully read it yet myself, but here it is, with the abstract:

https://iris.unica.it/retrieve/e2f56eda-a15d-3eaf-e053-3a05fe0a5d97/Articolo%20Between%20pubblicato.pdf

Full text is italian, but the abstract, partly copied here, is English:

"By comparing the urban sociology of the 1980s and 1990s, and the most recent theories produced in the field of Internet studies, this article aims to demonstrate that the platform society in which we live today – and its most dystopian drifts – had already been anticipated and prepared by the urban reconfiguration that took place, especially in the United States starting from the 1950s, with the housing form of Suburbia."

So, from the abstract, it seems that, calling my piece a genealogy that links medieval cities to current social media, that piece is an in-depth look at the next to last link of that chain. REALLY interesting, I'm going to contact the author right away!